Don’t miss this sensational travel narrative featuring Rosemary J. Brown, a UK-Canadian-American journalist following the swift footsteps of pioneering journalist Nellie Bly who raced around the world in 1889 to beat the 80-day record of a fictional character.

Local History Groups :: Lead Systemic Change

|

Regrowth in Lava

Mid-November, 2018

Four months after the lava ceased flowing, I walked over the narrowest part of the River of Lava which is several miles east of our farm. As I carefully tapped my way across the hardened lava, I noted signs of regrowth. The trees burned and pushed over by the force of the lava would not grow back, but seeds and spore already were growing.

Mid-May, 2019

At last, we are granted access to the property. After completing and signing extensive waivers, we are allowed to drive across the PVG (geothermal energy) property and other private gravel and cinder lanes to reach the farm. It’s been 50 weeks since the lava flow started and 63 weeks since it ended. The dense mass of small trees, big-leaf weeds and cane grass is astonishing and intimidating. If we can’t cut it back, seeds will spread and increase the dense underbrush.

Living the Dream on Hawai’i Island

The Lava has come and gone, as it has for millions of years. Some folks are heading back to the mainland or Alaska after losing their homes to the will of Pele, goddess of lava. Many farm families shrug off the inconvenience of access roads to markets that are still blocked by lava. They continue planting and harvesting, bringing papayas and avocados, rambutan and coconuts to the farmer’s markets or commercial merchants in Hilo. Everyone in the farming community hopes the local authorities will rebuild all major roads instead of routing dump-trucks, short-bed trucks and cars along narrow forest tracks better suited for bicycles and pedestrians. Surely, the roads will be repaired as in other disaster areas in the United States. Change is part of life; everyone copes.

People still dream of living on this mostly rural island and they are snapping up property. The Island of Hawai’i attracts newcomers and people from other parts of the state because of its relatively lower cost of living compared to Honolulu and Oahu. Puna, the southern district on Hawai’i Island affected by the 2018 lava flow, is said to be one of the fastest growing area on Big Island. The skies are clear again, the lava gone, quakes finished and the living is easy as long as the creek doesn’t rise or the feral pigs return..

Some families are leaving the island, selling their dream houses and businesses. Others changed their lifestyle and moved closer to Hilo, trading fire ants for fine arts.

One friend is headed back to Europe. She is selling her gorgeous one acre estate with splendid house and many ornamental trees, notably a mature Bismarckia palm.

Bismarckia nobilis is a slow-growing majestic tree named for the first chancellor of the German Empire Otto von Bismarck. The is particularly poignant to me because with considerable effort, I dug the hole for my own small Bismarckia palm a few years ago. The space needed for my young palm and its bulbous root system was about 61 cm (24 inches) deep by 61 cm across which I excavated with an oho bar for leverage through dense lava rock from the 1955 lava flow.

Alas, my Bismarckia perished in 2018 because of poisoned air during the lava inundation. Lava didn’t smother or burn it, the noxious VOG , a by-product of the eruption, killed the palms, ornamentals and hundreds of other trees.

After the Lava Sleeps

Are Railways in Peril?

National Rail Networks :: A Look Back in Time

The world’s first national rail networks were constructed in Britain, with the first inter-city line connecting the industrial midland city Manchester with the port of Liverpool in 1830.

So, are you wondering, which country forged a national rail network next? France? Sweden, the United States?

It was Egypt. The Egyptian rail system connected ports on the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea until the Suez Canal was opened in 1869. Egypt’s rolling stock is still on track. A recent issue of Future Rail magazine reports on Egypt’s recent purchase of 1,300 new carriages.

U.S.A.

In the 21st century some countries like the United States of America are not keeping up a commitment to passenger rail systems.

That’s a shame because rail travel offers faster, more efficient and ecologically favorable long distance travel than commercial airlines or private vehicles. Assuming, of course, the nation-state or region maintains and supports its railway systems.

A close look at an inventory of Amtrak rolling stock looks like an old used carriage auction block. Check out the fancy Amtrak advertising videos promising sleek, fast locomotives in the northeast corridor of the country, the most reliable profit center. Don’t wait in line or online for a ticket because it’s fantasy at this point. Why aren’t the U.S. leaders embarrassed by their poor showing compared to the lightning speed trains of Japan, France, Germany and other European countries?

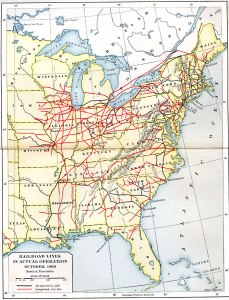

Back in the mists of time, the northern states of the U.S. had established a robust network of rail lines that connected with existing waterway transport and ports before the American Civil War. The southern states also built railways, but the lines dead-headed inland rather than featuring radiating lines that used hubs to interconnect with other railways. The absence of a connected rail network in the south was a factor in defeat.

President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act into law on July 1, 1862. This progressive action authorized construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. American continental railroads, built by immigrant laborers, usually under cruel and dangerous conditions, were instrumental in opening the western wilderness to travel and trade.

FRANCE

I’ve spent more time and kilometers riding the SNCF railway system in France than any other country. My first rail trip there was in 1966 on the boat-train from Calais (or was it Boulogne?) to Paris. The wider-gauge British trains left passengers at the ferry dock and after the Channel crossing, you’d walk to the French carriages for outward bound destinations. In the past I would ink my train travel routes on a map of France but the lines crossed and recrossed over the years to the point of obliterating the journeys and connections.

France built short rail lines to serve the mining industry. Agricultural communities resisted rail development arguing it would infringe on France’s well-organized transport network of canals and other waterways. Construction of long distance rail systems for commercial and consumer use started after 1842 with a network that could move goods for long distances overland.

RUSSIA

Russia, with distances far greater than the U.S., opened a single railway line from Moscow to St. Petersburg in 1851. With more land distance than the U.S. to cover, and few or no western and southern ports, Russia understood the value of connecting the capital and to ports in the Far East. Russia opened the Trans-Siberian Railway in 1916, though portions of the railway were functioning as early as 1903.

MEXICO

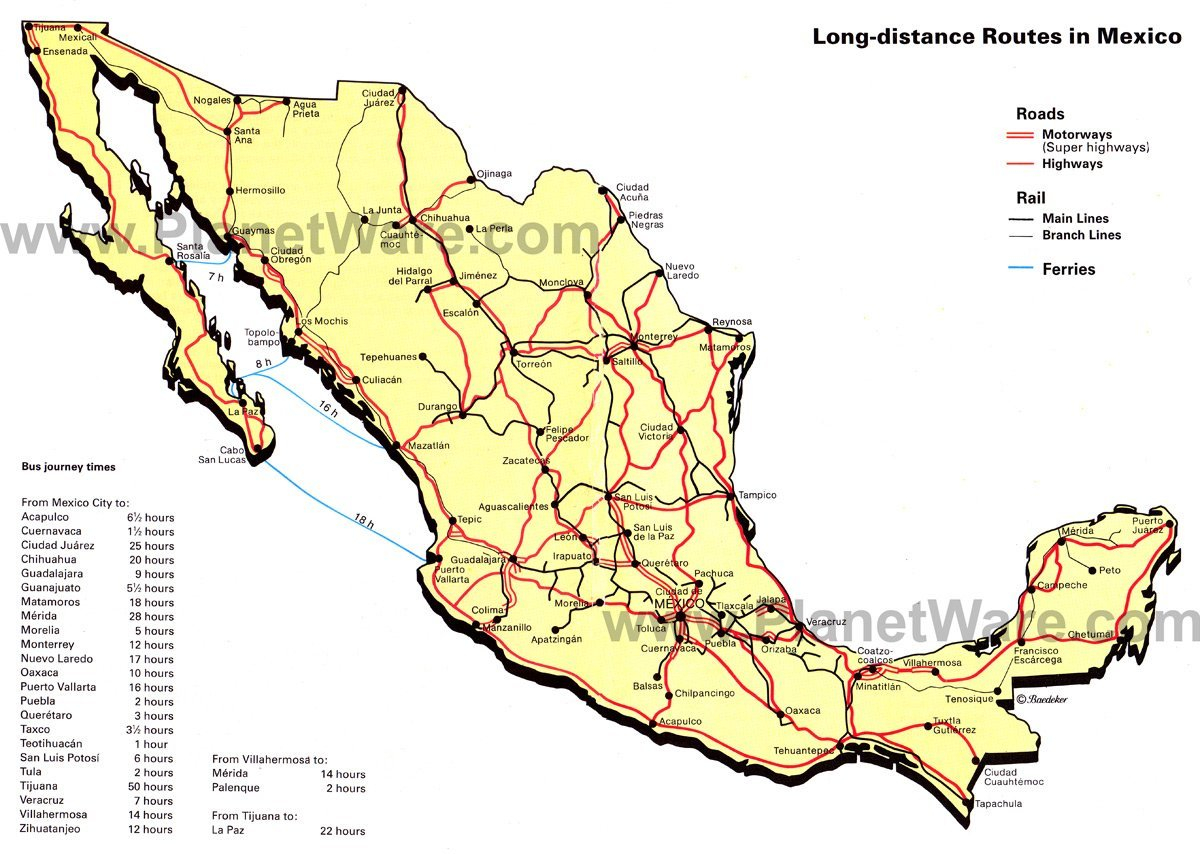

My experience with Mexico’s Railway Network is limited. During the early 1980’s, possibly 1981, my friend Don Tito and I boarded the Mexican railway by taking a Greyhound or Trailways bus from San Diego to El Centro, California and walking across the frontier to a train station in Mexico. I should consult a travel diary from that year to report the distances and ticket cost. I do not recall seeing a border wall at that time. The Pacific and Southwest Railway Museum in Campo, California owns carriages and locomotives of the San Diego and Arizona Railway that resemble the historic rolling stock we rode south through Mexico in 1981.

We boarded the Mexican long distance train at a town just steps across the border that took us all the way south to Mazatlan, a gritty seaport opposite the tip of Baja. I do not need to see again. The train ride took two days and nights. Or maybe it just seemed that long. It slowed to a long halt at towns so locals boarded to sell tamales, soft drinks and chiclets out of plastic buckets lined with heated towels to keep the food warm.

Decades later, I lived in Mexico City and wanted to explore the country by train, but during the 1990s, the government had consolidated or terminated most passenger rail systems. Apart from a couple of tourist trains that run limited, scenic routes and a commuter rail system serving the capital city, Mexico’s passenger rail service is a distant memory.

Occasionally, proposals arise to create new passenger rail lines or high-speed rail links between major cities. But proposals are not reality. Until some future date, the inter-city express bus service is adequate, sometimes stellar, but environmentally inefficient.

Ride on, rail enthusiasts!

Museum of Political Corruption

Check the transparency and ethics of government and corporate management daily. Maybe hourly?

Teachers, create a popular lesson by displaying the reach and excesses of political corruption all the way into the classroom.

Random browsers, visit the Facebook presence of the Museum of Political Corruption

No building is big enough to hold the documented and undocumented malfeasance of politicians and their money-bag cronies. Mr. Big, and Mrs. Big too, built their short-cut to the big-top on a pile. They usually don’t get caught; throw their myrmidons out as distraction bait.

The Museum of Political Corruption will be located in Albany, a city-state capital thought to be the bedrock of American political corruption. Maybe the museum library will be interested in maintaining print and digital archives of reporting on political corruption. Some writers and journalists have deep troves of subject files long predating the Internet.

Fortunately, investigative reporters like Susanne Craig of The New York Times are on the case. In May, 2017 Susanne Craig was named first winner of The Nellie Bly Award for Investigative Reporting.

Reporter Susanne Craig’s mailbox mysteriously yielded leaked pages from Donald Trump’s 1995 tax return. A former Albany bureau chief for The Times, Susanne Craig has also led investigations into allegations of wrongdoing in state government, such as New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s decision to shut down a much-heralded commission investigating public corruption.

The Museum of Political Corruption established the Nellie Bly Award to recognize the vital role investigative reporting plays in government oversight and maintaining an informed electorate. The award is named after late 1800s pioneering investigative reporter Nellie Bly.

Footsteps of the Saint-Simonians in Cairo

When I visited Cairo in 2013 the Arab Spring had not yet devolved to utter bloody chaos throughout the region, though anyone could see the trend.

In Cairo I sought the Franciscan Friars’ Oriental Studies Library intent on researching the pioneering men and women who traveled from France to Egypt in 1833-34 with Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin. The French group of adventurers were members of a social reform movement (sometimes described as a sect) known as Saint-Simonianism. Their philosophy originated in the writings of the Comte Henri de Saint-Simon, a proto-socialist aristocrat focused on improving education for working people, removing the influence of the Roman Catholic church on private life, and replacing marriage inequality with rights for women and family alliances outside of civil or religious certification. We would call that common law marriage or a civil partnership, but the conservative French government and the church described it as “free love” and jailed the Saint-Simonian leader Enfantin with a handful of others for inciting revolutionary ideas.

Soon, these French idealists were heading to the middle east with vague plans to to discover a female Messiah to balance the Christian emphasis on the male Messiah. On that pursuit they were unsuccessful.

However, Saint-Simonian ideas did influence other areas of French social structure, finance, and public transportation during ensuing decades. Their work in Egypt was especially notable and enduring.

Scientists and engineers, doctors, midwives, and educators affiliated with Saint-Simonianism worked under the aegis and with the approval of Muhammad Ali, the Egyptian Viceroy, to establish or improve and modernize the infrastructure of Egypt. Saint-Simonian efforts included building a medical school and the military training infrastructure, preliminary work on the Suez Canal, midwife training for local women and children’s education.

While in Cairo and Alexandria, many of the French men and women died during cholera and typhus epidemics during 1834-35 and 1836. I hoped to find their tombs.

My prior reading suggested that some tombs of the dead French idealists were located in the cloister of the Franciscan Monastery. In particular, Jehan d’Ivary, author of the 1928 travel book Promenades a Travers du Caire, which I examined in the Municipal Library in Toulouse in 1982, stated that a few Saint-Simonian workers were buried at the Monastery of the Franciscan Fathers, at the Hospital Abou Za`abal, and other locations, but that it was impossible to discover the locations of other French graves from that distant time.

In the 1830s Abou Za`abal was the Egyptian army hospital, but 170 years later, it was one of Cairo’s prisons and a short–or long term–compound for those ruled to be on the wrong side of the Arab Spring demonstrations. Abou Za`abal made international headlines in August, 2013 when dozens of prisoners perished as fully reported in the Guardian newspaper in February, 2014.

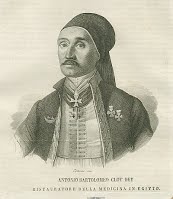

I arrived at the Franciscan Center of Christian Oriental Studies Library when the head priest was having lunch, or praying, or resting — I wasn’t certain of the explanation. Seeing my disappointment, the French-speaking library manager graciously invited me to use the library and perhaps return tomorrow when I could talk to the priest about the history of the Franciscan Monastery. Always at home in a library, I fingered through the card catalog searching for names of the French engineers, doctors, teachers, and other Saint-Simonian personnel. Without my laptop at hand, it was hit or miss to recall the correct spellings of the French immigrants from long ago. Eventually I found a trove of catalog cards citing books by or about the French-trained Doctor of Medicine and of Surgery, Dr. B. A. Clot (known in Egypt as Clot-Bey) who was the founder of Western medical systems in Egypt. After submitting a few book request cards to the library manager, I soon was paging through a copy of La Peste written by Dr. Clot-Bey. It was published in Paris in 1840 detailing his observations and experiments with quarantain during the frequent cholera outbreaks during the 1830s. I began scribbling notes

As Surgeon-in-Chief of the Armies and founder of the medical school in Cairo, Dr. Clot-Bey was awarded the honorific “Bey” by Muhammed Ali, the Viceroy of Egypt, and excused from pledging fealty to the Viceroy or the Muslim religion. At the time, Egypt was subject to the rule of the Ottoman Empire in Constantinople, but Muhammed Ali was in charge and had visionary ideas about improving Egypt. Dr. Clot-Bey selected and trained medical officers for the Egyptian army hospital founded in 1827 as Qasr al-‘Ayni School of Medicine.

Religious leaders at the time resisted the perceived threat of modern medical treatments and practices. Examination and autopsies of cadavers were considered insults to the body and prohibited in the Koran. Women could not be seen or touched by male doctors. The persuasive power of the Viceroy brought gradual change, but male medical doctors trained at Clot-Bey’s institution were forbidden to treat Egyptian women. The Viceroy asked Dr. Clot-Bey to found the maternity school for midwives which began training hakimas (Egyptian medical women).

During the decades of my interest in the Saint-Simonian women and their early feminist social movement, I have read and accumulated information about those who traveled to Egypt to teach hygiene and midwifery. In her memoir of the Saint-Simonian women in Egypt, the French midwife Suzanne Voilquin, mentions Dr. Clot-Bey as teacher and mentor. She later traveled and worked in Russia as a midwife.

Dr. Clot Bey was concerned with public health issues for containment and treatment of cholera and typhus as well as the childbirth mortality. His influence led directly to the foundation of a separate medical school for women and training midwives in Cairo. Dr. Clot-Bey’s thesis for the Doctor of Surgery awarded in 1823 by the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Montpellier was “Dangers of the Instrumental Manipulation in Obstetrical Delivery.” Even in the 21st c. infants and mothers remain at risk of damage and death from forceps manipulation.

What ultimately made this visit to the old Franciscan Monastery library so important to me was holding the book La Peste. The library ‘s copy was inscribed by Dr. Clot-Bey himself. Dr. Clot-Bey’s book brought out of the stacks for me to explore and read was an 1840 gift to the Monastery with the author’s signature in brown ink, copperplate script. The covers had been wrapped in different paper. I expressed surprise and appreciation to the library manager who reminded me to return the next day to meet the director.

When I returned the following day, I enjoyed an hour or so with the head of the monastery who listened to my research project and counseled that it would be nearly impossible to find tombs, graves, or headstones from nearly two hundred years ago. But he did have handwritten ledgers of deaths which I could peruse.

He disappeared for a while and I returned to claim a table in the small reading room area of the library. At another table a woman student was participating in a language reading lesson in a low voice while a senior man, possibly her father or other relative, observed looked on. This was familiar; I’ve taught English to immigrants in Maryland libraries, though parental escorts weren’t required. Soon the director brought out a stack of fat bound ledgers recording deaths of people from the international community living in Cairo from 1833 to 1836 who were in some way affiliated with the monastery’s church. Most of the deaths recorded in the large ledgers were due to cholera but I noted there was an occasional drowning or street accident. The nationalities of the deceased included citizens of Syria, Lebanon, Greece, Turkey, England, Italy, Spain and France.

The author in appropriate disguise.

The handwriting in the ledgers was difficult to decipher, and the script changed when one recorder succumbed to cholera which a note in the ledger explained with emotional emphasis. I managed to find records of a few French residents and even a doctor who was part of the Saint-Simonian group and died during the cholera epidemic, as Dr. Clot-Bey details in his book.

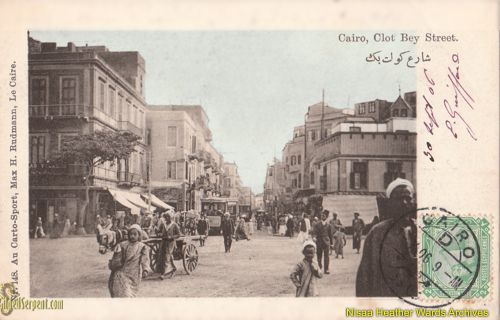

A significant street in Cairo is named Clot-Bey, depicted below on a 19th c. postcard from the Gilded Serpent website.

Ultimately, I wandered through a cemetery in the old Coptic section but none of the dates on grave markers extended to the 1830s. I contented myself with the timeless connection of using a book handled and inscribed by Dr. Clot-Bey, reward enough for my effort.

Resources:

Burrow, Gerard N. “Clot-Bey: Founder of Western Medical Practice in Egypt.” The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine: 48, 251-257 (1975) .

M. Paul Merruau, ”L’Egypte Contemporaine de Mehemet-ali a Said Pacha”, Paris, Librarie Internationale, 1860, p. 84.

Myntti, “Medical Education: The Struggle for Relevance”. Middle East Report, V:161

Clot-Bey, Antoine-Barthelemy. “De La Peste Obseré en Egypte.” Paris: 1840.

No White Food

Railway Museum in Cairo Reopened

In March, 2016 the Egyptian Railway Museum reopened.

Photo Gallery of the renovated museum.

Nearly three years ago, during May 2013, while visiting Cairo, I planned to see the Egyptian Railway Museum which occupies a portion of Ramses Station on the edge of a vast area of traffic flyovers, market stalls and vehicle congestion.

A colossal statue of Ramses in the busy plaza is a visual landmark if you arrive by taxi.

At the time I visited, an antique locomotive, part of the Egyptian rail network built by Scotsman Robert Stephenson, was displayed in front of the train station. The Stephenson family produced notable civil engineers, designers of railroads and bridges. The other Stevenson family — of writer Robert Louis Stevenson — were lighthouse designers and engineers.

Signs in the plaza pointed to the museum inside the station. As I walked closer, I saw the railway museum was in a state of deplorable ruin with massive piles of rubble outside, windows broken out, and an abandoned dozer tilting on piles of broken stones and tile. The museum building was a wrecked shell. Was a renovation project placed on hold because of the disruption caused by deep-seated unrest back in early 2011? Or was the building destroyed as a byproduct of cultural editing and property destruction undertaken during the “Year of Morsi” ? I could only wonder.

Fast forward a few years. A follower of this blog named Davy posted a comment with the photos of the reopened museum. I haven’t had the opportunity to return to Cairo since 2013, but the freshly opened railway museum offers an incentive.

The world’s first national rail networks began in Britain, with the inter-city line connecting industrial midland Manchester with the port of Liverpool in 1830.

Egypt forged a national rail network next. France had short rail lines in place, but not an network that could move goods long distance overland. Egypt’s rail system connected ports on the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea until the Suez Canal was opened in 1869.

Egypt’s initial railway track was built between Cairo and Alexandria. By 1856-1858, Egypt had a functioning railway network, which fitted the British interest in keeping the region stable and to secure faster communications and transport routes to India, the crown jewel of British colonial resources.

Britain tended to support the Ottoman Empire (which in theory ruled Egypt at the time) against all challengers, while British merchants nosed out commercial opportunities in the Nile Valley and Suez. An overland route opened between the port of Alexandria and the Gulf of Suez and the rolling stock and engine designed by Stephenson improved the route.