When I visited Cairo in 2013 the Arab Spring had not yet devolved to utter bloody chaos throughout the region, though anyone could see the trend.

In Cairo I sought the Franciscan Friars’ Oriental Studies Library intent on researching the pioneering men and women who traveled from France to Egypt in 1833-34 with Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin. The French group of adventurers were members of a social reform movement (sometimes described as a sect) known as Saint-Simonianism. Their philosophy originated in the writings of the Comte Henri de Saint-Simon, a proto-socialist aristocrat focused on improving education for working people, removing the influence of the Roman Catholic church on private life, and replacing marriage inequality with rights for women and family alliances outside of civil or religious certification. We would call that common law marriage or a civil partnership, but the conservative French government and the church described it as “free love” and jailed the Saint-Simonian leader Enfantin with a handful of others for inciting revolutionary ideas.

Soon, these French idealists were heading to the middle east with vague plans to to discover a female Messiah to balance the Christian emphasis on the male Messiah. On that pursuit they were unsuccessful.

However, Saint-Simonian ideas did influence other areas of French social structure, finance, and public transportation during ensuing decades. Their work in Egypt was especially notable and enduring.

Scientists and engineers, doctors, midwives, and educators affiliated with Saint-Simonianism worked under the aegis and with the approval of Muhammad Ali, the Egyptian Viceroy, to establish or improve and modernize the infrastructure of Egypt. Saint-Simonian efforts included building a medical school and the military training infrastructure, preliminary work on the Suez Canal, midwife training for local women and children’s education.

While in Cairo and Alexandria, many of the French men and women died during cholera and typhus epidemics during 1834-35 and 1836. I hoped to find their tombs.

My prior reading suggested that some tombs of the dead French idealists were located in the cloister of the Franciscan Monastery. In particular, Jehan d’Ivary, author of the 1928 travel book Promenades a Travers du Caire, which I examined in the Municipal Library in Toulouse in 1982, stated that a few Saint-Simonian workers were buried at the Monastery of the Franciscan Fathers, at the Hospital Abou Za`abal, and other locations, but that it was impossible to discover the locations of other French graves from that distant time.

In the 1830s Abou Za`abal was the Egyptian army hospital, but 170 years later, it was one of Cairo’s prisons and a short–or long term–compound for those ruled to be on the wrong side of the Arab Spring demonstrations. Abou Za`abal made international headlines in August, 2013 when dozens of prisoners perished as fully reported in the Guardian newspaper in February, 2014.

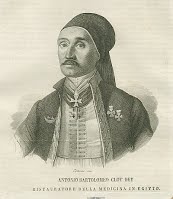

I arrived at the Franciscan Center of Christian Oriental Studies Library when the head priest was having lunch, or praying, or resting — I wasn’t certain of the explanation. Seeing my disappointment, the French-speaking library manager graciously invited me to use the library and perhaps return tomorrow when I could talk to the priest about the history of the Franciscan Monastery. Always at home in a library, I fingered through the card catalog searching for names of the French engineers, doctors, teachers, and other Saint-Simonian personnel. Without my laptop at hand, it was hit or miss to recall the correct spellings of the French immigrants from long ago. Eventually I found a trove of catalog cards citing books by or about the French-trained Doctor of Medicine and of Surgery, Dr. B. A. Clot (known in Egypt as Clot-Bey) who was the founder of Western medical systems in Egypt. After submitting a few book request cards to the library manager, I soon was paging through a copy of La Peste written by Dr. Clot-Bey. It was published in Paris in 1840 detailing his observations and experiments with quarantain during the frequent cholera outbreaks during the 1830s. I began scribbling notes

As Surgeon-in-Chief of the Armies and founder of the medical school in Cairo, Dr. Clot-Bey was awarded the honorific “Bey” by Muhammed Ali, the Viceroy of Egypt, and excused from pledging fealty to the Viceroy or the Muslim religion. At the time, Egypt was subject to the rule of the Ottoman Empire in Constantinople, but Muhammed Ali was in charge and had visionary ideas about improving Egypt. Dr. Clot-Bey selected and trained medical officers for the Egyptian army hospital founded in 1827 as Qasr al-‘Ayni School of Medicine.

Religious leaders at the time resisted the perceived threat of modern medical treatments and practices. Examination and autopsies of cadavers were considered insults to the body and prohibited in the Koran. Women could not be seen or touched by male doctors. The persuasive power of the Viceroy brought gradual change, but male medical doctors trained at Clot-Bey’s institution were forbidden to treat Egyptian women. The Viceroy asked Dr. Clot-Bey to found the maternity school for midwives which began training hakimas (Egyptian medical women).

During the decades of my interest in the Saint-Simonian women and their early feminist social movement, I have read and accumulated information about those who traveled to Egypt to teach hygiene and midwifery. In her memoir of the Saint-Simonian women in Egypt, the French midwife Suzanne Voilquin, mentions Dr. Clot-Bey as teacher and mentor. She later traveled and worked in Russia as a midwife.

Dr. Clot Bey was concerned with public health issues for containment and treatment of cholera and typhus as well as the childbirth mortality. His influence led directly to the foundation of a separate medical school for women and training midwives in Cairo. Dr. Clot-Bey’s thesis for the Doctor of Surgery awarded in 1823 by the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Montpellier was “Dangers of the Instrumental Manipulation in Obstetrical Delivery.” Even in the 21st c. infants and mothers remain at risk of damage and death from forceps manipulation.

What ultimately made this visit to the old Franciscan Monastery library so important to me was holding the book La Peste. The library ‘s copy was inscribed by Dr. Clot-Bey himself. Dr. Clot-Bey’s book brought out of the stacks for me to explore and read was an 1840 gift to the Monastery with the author’s signature in brown ink, copperplate script. The covers had been wrapped in different paper. I expressed surprise and appreciation to the library manager who reminded me to return the next day to meet the director.

When I returned the following day, I enjoyed an hour or so with the head of the monastery who listened to my research project and counseled that it would be nearly impossible to find tombs, graves, or headstones from nearly two hundred years ago. But he did have handwritten ledgers of deaths which I could peruse.

He disappeared for a while and I returned to claim a table in the small reading room area of the library. At another table a woman student was participating in a language reading lesson in a low voice while a senior man, possibly her father or other relative, observed looked on. This was familiar; I’ve taught English to immigrants in Maryland libraries, though parental escorts weren’t required. Soon the director brought out a stack of fat bound ledgers recording deaths of people from the international community living in Cairo from 1833 to 1836 who were in some way affiliated with the monastery’s church. Most of the deaths recorded in the large ledgers were due to cholera but I noted there was an occasional drowning or street accident. The nationalities of the deceased included citizens of Syria, Lebanon, Greece, Turkey, England, Italy, Spain and France.

The author in appropriate disguise.

The handwriting in the ledgers was difficult to decipher, and the script changed when one recorder succumbed to cholera which a note in the ledger explained with emotional emphasis. I managed to find records of a few French residents and even a doctor who was part of the Saint-Simonian group and died during the cholera epidemic, as Dr. Clot-Bey details in his book.

A significant street in Cairo is named Clot-Bey, depicted below on a 19th c. postcard from the Gilded Serpent website.

Ultimately, I wandered through a cemetery in the old Coptic section but none of the dates on grave markers extended to the 1830s. I contented myself with the timeless connection of using a book handled and inscribed by Dr. Clot-Bey, reward enough for my effort.

Resources:

Burrow, Gerard N. “Clot-Bey: Founder of Western Medical Practice in Egypt.” The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine: 48, 251-257 (1975) .

M. Paul Merruau, ”L’Egypte Contemporaine de Mehemet-ali a Said Pacha”, Paris, Librarie Internationale, 1860, p. 84.

Myntti, “Medical Education: The Struggle for Relevance”. Middle East Report, V:161

Clot-Bey, Antoine-Barthelemy. “De La Peste Obseré en Egypte.” Paris: 1840.